When I found Roy, he was already dead.

When I found Roy, he was already dead.

A scream rose like bile in my throat. I swallowed it with a choking gulp.

Making a sound was not an option.

If they hear me, they will find me. Then I’ll be dead too.

His mouth was frozen in what appeared to be an uncomfortable mix of smile and scream. It was the type of expression that comes when a close friend jumps out from behind a corner and yells “Boo!” You know it’s a joke. You know you are in no real danger. But something inside you – something primal, something unconscious – believes this could be the end. Suddenly, you are stripped down to the basic human condition: fear and confusion.

Where Roy’s eyes had been were now bubbling pits of putrefied gore. His face was cut to ribbons and deep impact divots had misshapen his skull into something unrecognizable. Something very close to a masterpiece, defiled.

Christian radio personality Frank Pastore was able to correctly announce the way he would die while doing a radio show one afternoon. Speaking to his adoring listeners, Frank, in a moment of serendipity, said over the air, “You guys know I ride a motorcycle, right? At any moment, especially with the idiot people who cross the diamond lane into my lane, without any blinkers — not that I’m angry about it — at any minute, I could be spread all over the 210.”

Three hours later, an elderly woman crossed into his lane and Frank Pastore was human mulch.

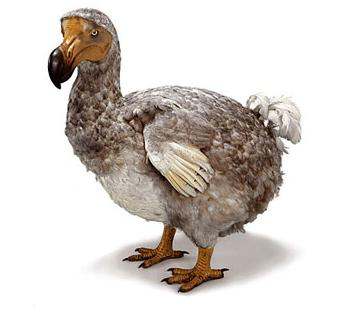

But, pecked to death by an extinct bird?

There is no way anyone could see that coming.

The four years of work it took bringing Raphus cucullatus, the Dodo bird, back to life had worn me down. Cracks had begun to form in the corners of my eyes. When I looked in the mirror every morning, my skin, my teeth, my nails, seemed be more tarnished than they were on the previous day’s examination.

The work wasn’t in bringing the birds into the world; that part is easy enough. A healthy spoonful of Dodo DNA extracted from a preserved skeleton, a dash of Nicobar Pigeon, Ostrich, and Albatross, a blast of electricity, and blammo! What once was not, is again. The work is in keeping them alive, playing the part of overbearing mother, long enough for them to breed naturally. It makes me sick to my stomach, rumbling with a combination of pride and revulsion, to think of the hours, the days, I spent sitting and watching respiration cycles, monitoring internal temperatures, examining fecal matter.

Now, I’m about to be killed by a marauding flock of the creatures I coddled like my own children.

I just needed a night out. I needed to blow off some steam. Get drunk. Get laid. Feel taken care of rather than feeling I must take care of. The office was a place dank enough to keep my colleagues away but still hip enough to draw in the 20-something frat boys looking to get wasted on the cheap. Roy had caught my eye when I was three vodka tonics deep. My low cut dress had caught his.

“Have you ever heard of the Dodo bird?” I asked, as flirty as one can utter that particular phrase.

My guts suddenly turned over the way they turn over when you make snap decision and know there is no turning back.

When Roy asked if he could see the birds, I shot him down at first. He was buying my drinks, and I was becoming less and less aware of the flaws in my veneer. Roy put his hand on my lower back and put his mouth close to my ear. The sensation of his breath against my skin reminded me of my womanhood.

“C’mon, show me, and then I’ll show you something afterwards,” Roy whispered.

All matriarchal inhibitions dissolved. We left.

The lab was dark when we pulled up. Not just closed-for-the-night-be-back-at-9-AM dark. Dark dark. Pitch black. I had figured a fuse had just popped. Inside, the hum of blue-white emergency lights lead us, stumbling, to the containment area.

The enclosures were empty. Every single male specimen was gone. At first, I thought it must have been a break in, that a competitor had caught wind of what we were doing and stolen the Dodos for fame or glory. Yet, each glass door, easily opened by anyone with at least one ooposable thumb, was smashed out from the inside.

“Looks like your extinct birds flew the coop,” Roy said with a chuckle.

“Dodo can’t fly,” I replied. “Stay here, Roy. I’ll be right back.”

That was the last time I saw Roy alive. When I returned from checking the other offices for any signs of life, poor Roy, his once pretty face all smashed and bashed and gouged into a thick red stew, was no more. Signs of panic were all around his body. Perfect red tridactyl imprints scattered in every direction, fleeing the scene of the crime, creating a web of violent victory that spread across the room and out the rear door.

Hhhh-nnawwk.

Hnn-ah-ah-ah-Hnwwkk.

A cacophony of percussive honks and broken glass blared from the female containment area. Keeping low and quiet, I crept to the viewing window on the adjoining wall. Inside some 50 or so supposed-to-be-extinct birds were mingling amongst twinkling bits of broken glass, honking and preening, courting mates through spastic head bobs and bounces. For a moment, I forgot all about the dead body that lay not 10 feet from where I stood, awestruck. I was a witness to a ritual that had not been viewed in 400 years.

The loneliness of the moment, the recollection of Roy’s touch, the echo of his laughter in my head, shook me from the state of mesmerized romanticism. Something had gone terribly wrong in our attempt to cheat natural selection. Dutch explorers described the Dodo as docile and fearless to a point of foolishness. Nowhere was it mentioned that they were blood-hungry.

I crept to the door, just slightly ajar, of the female containment room. Keeping my eye on the birds through the reinforced glass window, I pulled the locking mechanism.

CLICK!

50 beady pairs of ink-black eyes were on me at once. The birds stood frozen in the previous moment of whatever courtship display they had begun.

I backed up, trembling and sweaty but slightly more at ease now that my homicidal brood was locked away. I turned my attention back to Roy. Pitiful, hapless Roy. I would be fired for sure. Not only had I brought a non-employee to a restricted genetics lab but also said non-employee was mauled to death by our crowning achievement.

THUD! THUD! THUD!

The damn things were flinging themselves at the viewing window.

THUD!THUD!THUD!THUD!THUD!

Before I could really gather what was happening, the glass was shattered and the birds, all 50 of them, standing three feet tall and weighing 22 pounds each, had washed over me, a wave of feather and talon and beak. In a frenzy, they dug and pecked and scratched at my eyes, my tongue, my neck, opened every main artery.

I was dead.

Extinct.

In my last moments, before the hooked beak of a fledgling to which I had given countless sleepless nights tore out my right eye, I imagined the horror and disappointment of my colleagues when they would find me in a few hours. I saw and felt the grief and anguish of my parents and friends when they would be telephoned by police bearing bad news.

I thought of rotting Roy lying beside me.

I thought of how some things are really better forgotten.

Christopher J. Feterowski resides in Boston, Massachusetts with his girlfriend Catherine and miniature schnauzer, Jules. By day, Christopher is an audio engineer, live production technician, musician, and blogger for Bruinslife.com. Christopher is currently working on his first novel titled, “Transmission” and hopes to have it completed sometime before the end of days. More of Christopher’s poetry and short stories can be found at http://anamericanlullaby.blogspot.com.